Of course, I have interacted with people from different classes in the past. But I had never had to seek help nor had I received kindness from someone whom one would describe as "poor."

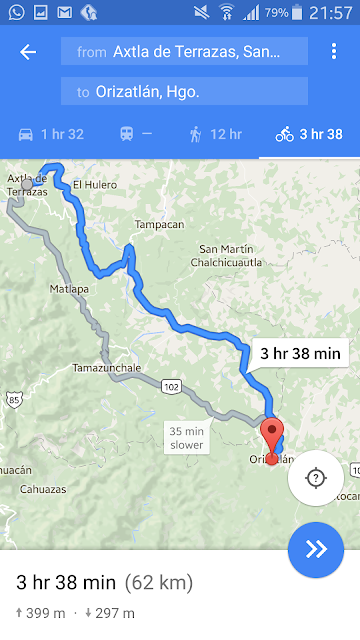

The gray line is the highway, i.e. a lot of traffic and no space for bicycles. I had no clue what the blue line was like, but it was far away from the main highway and, therefore, from traffic. I decided to take that route.

Before setting out, I noticed that the tyres could do with some air. However, the airpump that I have did not quite work. I set out anyway.

The blue line turned out to be mostly dirt roads such as these:

I cursed Google when Brownie crashed because of too much gravel downhill. We came out unscathed.

Thankfully, the dirt roads ended when I exited a small village called, El Cerro.

The paved road led me through these ranches. I hardly saw any people for the next few kilometers.

The humidity made it difficult to bike. I stopped at this small shop run by a lady for a snack. She offered some blueberry water for free.

The village had a bilingual school. I assumed they taught in Spanish and Nahuatl.

I turned towards Tampacan at about 3:30pm. A few kilometers later, a guy came up to me in his bike. He wanted to know what I was up to with all that load on my bike. He pointed out that the posterior tyre needed more air and offered to take me to his place where we could use his airpump. He lived just a 100 meters away. Here:

He suggested that I go back and take the highway instead if I wanted to reach Orizatlan that very day. I told him how difficult it had been to bike on that highway on my way to Axtla from Xilitla. He and his family wished me luck.

I then cycled through these landscapes:

After some tough uphills on rocky roads (Brownie tripped again), I reached a village called, La Mesa del Toro:

The main road in the village was a paved one, but not too long after crossing the river, it was once again a very long dirt track, except this steep cemented track that ran through a remote village nestled in the hills:

I thought of camping in the village. But something kept me going further.

The rest of the road ran through thick vegetation on both sides. It almost seemed as if I was biking through a forest, and I probably was. I did not see another person for a very long time. Since I was in a hurry, I did not stop to click too many pictures. All I remember is that the sun was about to set and I was still quite far from my destination.

Finally, I emerged from the forest onto a road that, according to a woodcutter, led to Chapulhuacanito or simply Chapul. The peremptory rule of travelling by bike in Mexico (and without a headlight) is that you don't pedal at night. I needed a safe place to camp. About 20 minutes later, I was at crossroads. I could continue on the blue line or take a detour to get to Chapulhuacanito or camp on the verdant pasture in front of me. Three kids passing by told me that the blue line would soon be a dirt road, the road to Chapul was a macadamised one. I could not decide which road to take. Something told me that I should just camp in the country. So I walked onto the green pasture towards the lone wooden hut on it.

There was a lot of farmland machinery under a huge tree. But I could not see any active agricultural activity; only lush green grass as far as my eyes could see. There was a trail with sparse grass that led to the hut. Clearly, somebody lived there. A dog, presumably of the owner of the hut, hesitantly barked. A man came out and then somebody behind him as well. They were both hesitant to come out, but by the time I was about five meters away from the hut, they eventually did. I smiled and began my usual spiel, "Hello beautiful people, I am from India. I am travelling by bike through Mexico. I wanted to get to Orizatlan today, but it's getting dark. You, as Mexicans, know better than me that it is unsafe to travel in the dark. I need a safe place to spend the night. I have my tent and mattress. I even have my own food. Rest assured I will not cause any trouble. All I ask for is a safe place to set up my tent and park my bike." The man nodded and said that it was not a problem, but he needed to ask his father who lived in the hut on the other side of the road. (I had seen the hut and noticed a boy was observing me, who I later got to know was his brother.)

I have been hosted by several strangers. And each time, there is a sense of fear that I need to assuage by talking, showing pictures of my travels, sharing my stories, inspiring kindness by telling a reluctant host how I had received kindness in the previous village or town. In cities, I contact people through travellers' networks that have different ways of establishing trust. In this case, they agreed to host me without asking me anything, without any attempt to verify if I was genuine, without me having to quell fear because there was none.

The man introduced himself as Julio. Julio's father arrived. He consented but asked me to put up my tent close to the hut and not too far away in the grass for the fear of snakes. I began pitching my tent. I was almost done when the father asked me if I had cold water. "You pedalled all the way from Axtla in such heat, you must be thirsty. I will go fetch a few bottles of cold water."

Then Julio asked me to move the tent under the shed behind their hut for it could get windy. He said that he would have liked to offer a bed but they only had one- for him, his wife and his daughter.

It was dark already. I told them I was about to have dinner.

"Wouldn't you join us? We can only offer eggs and tortillas, but we would like if you joined us for dinner," said Julio's wife, Chela.

Chela made the tortillas on a wood stove while Julio went to the nearest village to buy canned chillies (I later learned that he actually tried to find chicken but at that hour could not.)

Those were the best tortillas I have had. Julio ate them like a chapati (Indian bread similar to Mexican tortilla). Chela had made quite a pile of tortillas. I was wondering why. After we finished eating, they fed their 6 dogs and 2 cats, and then I understood why.

Chela told me about the different dialects of Nahuatl. I was showing off the few words of Nahuatl that I had learned from an old man in a village called El Nacimiento. She informed me how Nahuatl is different in her village, which is about 25 Km away, and the nearest one. She told me the exact differences in how people would speak the words that I had learned in those two villages. It was fascinating to learn how that language changed within very short distances. I asked her if Nata was learning Nahuatl. Unfortunately, not. Those bilingual schools are not bilingual after all. Chela was, despite her circumstances, well informed through television. She knew about elephants and tigers in India. They were quite curious. They would tell me something about Mexico and then ask me if India was different in that regard- we mostly focused on religion and food. They asked me if we baptize kids in India. I told them that the Christians do but the Hindus don't. They have a ceremony instead where the head of a kid is shaved. I asked Nata if she had friends in school. To my surprise, she said that she did not. I asked her why. Chela reasoned, "Bulling" (Interestingly, bullying has made its way into Mexican Spanish).

In the morning, I woke up to their rooster's cockadoodledoo at 9:30. I could hear Chela trying to scare the rooster away so it would not wake me up. I thought I could catch a few minutes of sleep. But somehow the rooster found its way to the other side of the tent and woke me up yet again, almost as if someone had entrusted him with that task. I thought I would have my breakfast cereal before leaving. But Chela had already made coffee. She also offered me some sweet breads. I thought breakfast was done. But no, Julio had gone out to find cheese made from cow's milk because the previous night I had mentioned how I missed the taste of Indian cheese made from cow's milk. So, they offered cheese with tortillas and, of course, chillies.

It was time to say goodbye. To breach the awkward silence that is characteristic of difficult goodbyes, Chela said, "Pues, hasta nunca entonces!" (Well, until never again I suppose.) That hurt. I joked, "Who knows! Maybe I will find a mexican, get married and settle here." She got all excited, "Really? Will you marry a woman from the Huasteca region or some other part of Mexico?" I just laughed. Julio's eyes were turning moist. Chela remarked, "Somebody is going to miss you." As men we could not have cried in the presence of women. I asked Julio for a hug. That was it. We could not hold our tears back. Julio kept saying, "May God bless you! May you have the time of your life!" Nata, poor kid, even she started crying. Chela stood there, smiling at us. I hugged Chela and Nata. I had nothing to offer to them; I could not have offered my used clothes or cycle repair tools and extra parts. I could have offered money even though I was low on cash. But offering any amount of money felt like insulting them. I am sure they were not expecting anything in return. With a lump in my throat, I said, "No quiero salir pero tengo que ir. Hasta luego, amigos!" (I do not wish to leave, but I must go. Goodbye, my friends.)

As I walked away from them, about 100 meters away, I had to turn my head around. Nata yelled out, "Estebaaaaaaan..." and came running towards me . "Estebaaaaaan..." she repeated. I hugged her and wished her the best of life ahead. Chela was standing in the distance, smiling.

I have no qualms about admitting that I could not bike for too long at a stretch that day. I had to stop frequently to clear my tearful eyes.

You might call Julio, his father, and Chela gullible for not probing me before agreeing to host me. But, you, like me, are not "poor." And, therefore, accustomed to live a life of fear. You see, Julio and his family had nothing to lose. Chela, in fact, joked right before going to bed, "I hope you won't rob us, Esteban, while we are asleep." The rich, on the other hand, constantly live in fear: the fear of being robbed- robbed of their acquisitions of mindless consumption and their borrowed dreams; the fear of losing to their friends, family and neighbours who have a better car, bigger and flatter television screen, a higher income or salary. Why acquire all that if the result is a crippled, helpless, and often, contrived, compassion for others and a life full of fear?

One of the firefighters who had offered me food, shelter, and friendship in Castaños, had rightly said, “Los que menos tienen, más dan." (Only those who have little are capable of giving a lot.) I wish each one of you get to meet people like Julio and his family at least once in your life. Because these are the people worth living for. And, if necessary, worth fighting for.

I shared my experience of biking on those dirt tracks with my Mexican cyclist friends whom I had recently met in Aquismon. I requested one of them, Santiago, to let me know if he decided to do that route ever and if he would be willing to carry a few gifts for Julio and his family. Santi, as he is belovedly called, is extremely passionate about cycling, nature, and giving. He and Marystelita have agreed to undertake this ride already! They will be on their way to that verdant pasture almost 250 Km away from their hometown, Tampico, on May 21st and will reach Julio's hut on May 22nd.

I cannot thank them enough. But for Santi, "Todos somos uno, amigo." (We are all parts of the same whole, my friend.)